Article

The palace turned hospital

A Forgotten Chapter: Indian Soldiers at Brighton’s Royal Pavilion in WWI

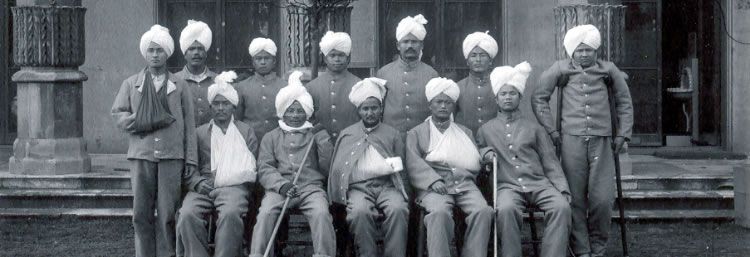

In 1914, the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, a grand seaside palace with domes and exotic decoration, was turned into a military hospital. But it wasn’t for local British troops. It was for Indian soldiers who had been injured while fighting in France and Belgium.

These men were part of the British Empire’s army. They were among the first people of colour to be treated on English soil during wartime. This is their story. A story of bravery, culture, care, and dignity, and a part of British history that deserves to be better known.

The Empire’s Soldiers on the Front Line

When the First World War broke out, Britain turned to its empire for support. India sent over a million men to serve. Around 90,000 were sent to Europe to fight alongside British and French troops. Many were injured in the first year of the war.

They came from many different communities, including Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims and others, and from places like Punjab, Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, and Nepal. Most had never left India before. They fought bravely in trenches, under constant attack, and in harsh winter conditions.

After months of fighting, thousands were injured. Hospitals in France were full, and British commanders wanted to offer better care. That care came in the form of a unique hospital, inside the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

Why the Royal Pavilion?

The Pavilion was no ordinary building. Built by King George IV in the 1800s, it was designed to copy Indian palaces. It had onion domes, decorative columns, and painted dragons on the walls. Some thought the Indian-style design might make the soldiers feel more at home.

In late 1914, the Pavilion and nearby buildings were quickly turned into a hospital. Beds replaced banquet tables. The royal kitchen became an operating theatre. The hospital opened in December 1914.

It could treat over 700 patients, and more than 2,300 Indian soldiers were treated in Brighton between 1914 and 1916.

Culture and Faith Were Respected

The authorities knew they had to respect Indian culture and religion if they wanted the soldiers to feel safe and dignified.

- Separate kitchens were set up for Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs.

- No pork or beef was served.

- Soldiers washed their own plates to keep caste practices intact.

- A Sikh gurdwara tent was set up in the garden.

- Muslim soldiers had a prayer space facing Mecca.

- Hindu soldiers had access to worship areas and religious books.

- Interpreters were on hand to help doctors and patients communicate.

A ‘caste committee’ made up of Indian patients advised staff. This level of cultural respect was rare during colonial times, but it helped the soldiers feel valued as people, not just patients.

Everyday Life for the Soldiers

The soldiers wore blue hospital uniforms and had their own beds, lockers and toiletries. They were treated with care by British nurses and doctors. Some were amazed at the attention they received.

They were given books, music, puzzles, and newspapers in Hindi, Urdu and Gurmukhi. A small publication, Akhbar-i-Jang (War News), was written by and for the Indian soldiers.

They went on outings to the countryside and the seaside. Some were even taken on day trips to London. Volunteers and local residents helped provide entertainment and gifts. For many soldiers, it was the first time they had experienced Britain outside of war.

One soldier wrote home:

“Do not worry about me. I am in paradise here.”

When the King Came to Visit

King George V took a personal interest in the Indian soldiers. On 1 January 1915, he and Queen Mary visited the Royal Pavilion Hospital. They walked through each ward, speaking to the injured men. The Queen gave gifts, and the King asked after their health.

This moment was hugely important. For many of the soldiers, the King Emperor was a distant figure, someone they had only heard about. Now he was standing at their bedside.

In August 1915, the King returned to present medals for bravery. Among those honoured was Jamadar Mir Dast, who received the Victoria Cross, the highest military award, for his actions under fire in Belgium.

What made this visit even more special was what happened afterwards. While leaving the Pavilion, the King heard Sikh hymns being sung in the garden gurdwara. He asked to attend. He stood quietly at the back of the service and joined the congregation in respectful silence.

One Sikh soldier later wrote:

“The King Emperor stood with us during our prayers. This is something I will never forget.”

The soldiers saw this as a great honour. It showed them that their culture and faith were being recognised at the highest level.

What Happened to Those Who Died?

Sadly, not all the soldiers survived their injuries. A total of 53 Indian men died while being treated in Brighton. The authorities ensured they were given proper funeral rites.

- Hindu and Sikh soldiers were cremated in traditional open-air ceremonies on the South Downs, just outside Brighton.

- Muslim soldiers were buried at the Shah Jahan Mosque in Woking.

This level of care was unusual and showed real effort to honour the men’s beliefs.

The Chattri Memorial

In 1921, a memorial was built on the exact site where the Hindu and Sikh cremations had taken place. It was named the Chattri, meaning “umbrella” in Hindi and Punjabi.

Made from white marble and built in traditional Indian style, the Chattri stands on a peaceful hillside overlooking Brighton. It was created to honour all the Indian soldiers who died in the area.

Each year, people gather at the Chattri to remember those men. Veterans, community groups, local people and faith leaders come together to lay wreaths and pay their respects. It is one of the most important South Asian war memorials in Britain.

For many British Asians, the Chattri is not just a monument. It is a connection to their history and heritage in the UK.

Why This Story Matters

The story of the Royal Pavilion Hospital is about more than medicine. It is about visibility. It shows that people of colour were part of Britain’s history long before Windrush, long before modern migration.

These men fought, bled and died for Britain. They were treated in a royal palace, received visits from the King, and were given space to practise their faith. At a time when racism and colonialism were widespread, they were treated, at least in this setting, with care and dignity.

Their story is part of our shared history. It belongs to British Asians, but also to anyone who wants to understand how people of different backgrounds came together in a time of crisis.

The Royal Pavilion, the Indian Gate, and the Chattri stand as reminders of service, sacrifice and respect. They tell a story of Indian soldiers who came to Britain not as strangers, but as protectors, and were met with kindness that mattered.

This is not just a Brighton story. It is part of the long and proud history of Britain’s Black and Asian communities.

Their place in the past should never be forgotten. Their contribution shaped the country we live in today.